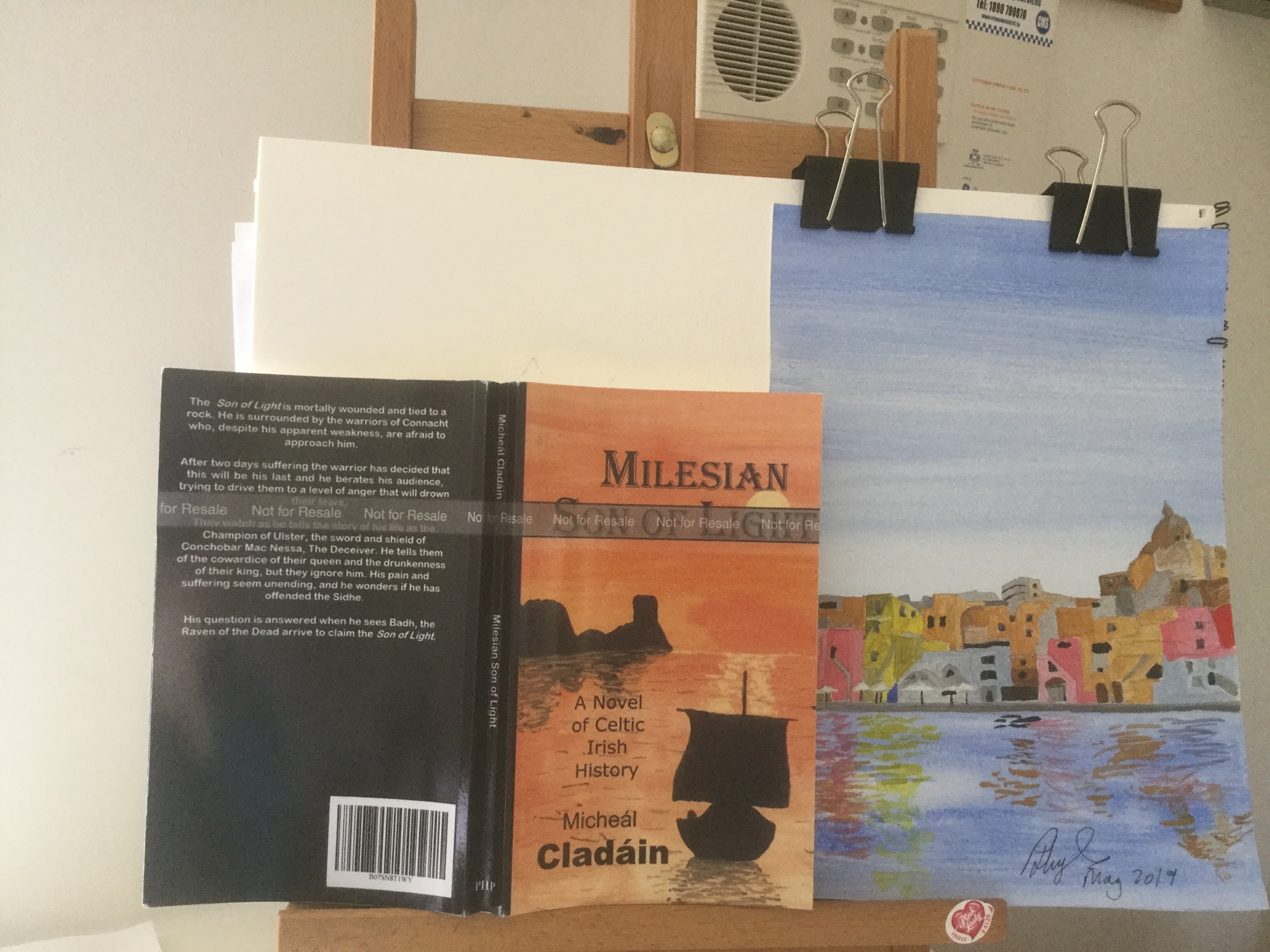

Hard at work with print proof

Milesian Son of Light – Available for Pre-Order

Milesian Son of Light – Trailer – Release Date July 3rd

Dawn

1

I see it in my mind as though it were yesterday. It seems strange, but now I can see the flapping of The Morrigan’s wings, everything that had become misty through time, I see with clarity. Although my eyes are dulled by pain, my mind is sharp as a boar spear. Yes, yes, your impatience is obvious in your fidgeting. I will tell all, but it will be in my own time. You can wait for my death but not for my story? But then you are waiting, aren’t you? You fear her too much to leave, and you fear me too much to act, I warrant.

So, to my tale.

It was late afternoon when I first met the warrior. The sun was falling slowly from the sky, approaching the eaves of the forest in the mountains where my father had chosen to hide us. It had been a normal day. Chores completed, I was hurling with Diarmuid and the others. Da was chopping wood and Ma was cooking, as she always seemed to be. Cooking or washing our clothes in the Dargle, anyway. I remember smelling the smoke of the cook fire and beginning to salivate over thoughts of fresh venison and oats, tiring of the game. I was just wondering if always winning could be as tiresome as never winning, and thought to ask Diarmuid, when he stopped and looked over my shoulder at the rise.

‘He looks like he has just fought a hard battle,’ he said with a nod.

I scoffed and shook my head. ‘You think I will fall for that, Diarmuid? I am not as thick as you think. You want the sliotar, you will have to take it by force.’

‘No, really, Seti. He has a bandage on his head and on his arm. His horse is skittish too. I swear on The Morrigan. He is a warrior.’

‘And what in the name of The Morrigan would a warrior be doing in this Gods’ forsaken dung heap? They have better things to do…’ and then a horse neighed, so I looked.

The man sitting at the top of the rise had the look of one in need of rest. The bandages were as Diarmuid had said, and blood-stained. He was one who had seen hard battles, I supposed. I had never seen a warrior before, hiding in the mountains because of the fears of my father, I had never seen anything of interest, let alone a warrior or a princess, a king or a queen. Those things, until that day, had been the stuff of my dreams and my father’s drunken stories.

‘Now, there is a warrior if ever I saw one,’ I said, with a knowledgeable nod.

‘What was I telling you. A warrior here in the Wicklow Mountains. Never thought I would see it happen. Blooded too.’

‘You think the rumours of invasion are true?’ I asked of no one. Travellers had been in the forest, running from reavers, they said. Da said they were just looking for a free meal and to ignore them. But seeing the warrior sitting at the top of the rise, I had my doubts.

My prayers that he would continue to the settlement were answered when the man kicked his horse into motion, and they started down the path. I stood my hurley between my feet and leant on it to watch him come. He seemed in no hurry the gait of his horse easy. My chest heaved with excitement. It was as though my life’s meaning was riding down the slope. I had thought I would spend my days tilling the hard ground, trying to make enough to live on, back bent by the labour, gut distended because of the mead necessary to forget the hardness of life, a wife and children on whom to beat out my frustrations.

As he neared, I could see he was no longer young. His hair was greying at the temples, below the dirty bandage. His bare forearms showed the scars of many sword strokes.

‘Are you straight from battle, warrior?’ I asked, as he reined in beside us. He frowned down. The sun was behind me, and I knew he could see little.

I was about to repeat my question when Diarmuid shouted, ‘Look Lámthapad,’ pointing at the red and black shield, where it was hanging over the horse’s rump. ‘It is the shield of the Ulster champion. Are you he, Conall Cernach, the captain of the Red Branch?’

‘Is it true? Have you just ridden from battle?’ I repeated.

‘Enough,’ the warrior’s voice carried power and we stopped, holding our collective breaths. ‘Who is chieftain of this settlement?’

‘My father,’ I said.

‘Which is your homestead, boy?’

‘It is there. The second one. You can see my father chopping wood,’ I pointed my hurley for emphasis.

The warrior said nothing more. He turned his horse in the direction of our small roundhouse and said, ‘Ride on, Dornoll.’ The horse obeyed with the same easiness she had shown walking down the slope. We abandoned our game and followed them, seeming to reach a silent agreement to go and listen. Whatever the warrior wanted it was bound to be of more interest than a tired game of hurling.

‘Well met, farmer,’ I heard the warrior say as he reined in his mount.

My father did not respond immediately but straightened his back as much as it would go and leant on his axe, one hand shielding his eyes from the setting sun.

‘And who might you be, stranger?’ he asked, in a tone that was in no way welcoming. ‘Or more to the point, what are you doing in my glen? There is nothing here for the high and the mighty.’

‘I am lost. Seeking my way to Tara.’

‘Over there, the deer track will bring you to Slíghe Chualann,’ da pointed his axe at the other side of the glen. ‘Follow it north and you will come to Tara. Good day to you.’

‘Da, da, look it is the champion of The Ulaid,’ I said, trying to delay the warrior’s parting.

‘I did not say I was the champion of anywhere, boy.’

‘If you are not Conchobar Mac Nessa’s man, why do you have Lámthapad hanging over your horse’s arse?’ da asked.

‘You seem to know a great deal for someone hiding in the Chualann forest,’ the warrior said, looking back at the shield with a frown.

‘I know enough to keep my family safe.’

‘How do you know it is Lámthapad? It might be a fake?’ Da shook his head and smiled. Even I smiled at the futile attempt of the warrior to keep his name to himself.

‘My brother is a blacksmith. I know white gold when I see it. If the shield is false, it is a very costly affectation.’ My father looked over at the darkening forest before turning back and saying, ‘The deer track is yonder. You should be on your way before night keeps you here in the glen,’ where you are not welcome, da’s eyes said, even though his mouth did not have the courage to utter the words.

I expected the warrior to drawer his sword or crush da’s head with the war hammer strapped across his back. Instead, he shook his head, sighed, crossed his wrists over the horn of his saddle and said, ‘I need a favour of you.’

‘What is it you want?’

‘What is it I want, man? As you rightly just said, night is upon us. I was looking for succour until the dawn. I have ridden long and hard with news for Tara.’

My father looked away, deep in thought. It was obvious he did not want to play host to a warrior known for his ability with all weapons, but nor did he want to offend. Like us all, da had heard of Conall Cernach. He probably thought he was standing before a man who would use the hammer resting across his back without thinking. My da surprised me then for the only time in my life. I had not thought it possible a vindictive and cowardly man would have it in him when he said, ‘You can sleep in the ox shed.’

‘The ox shed…’ the warrior started, his hand drifting towards the hilt of his sword.

‘I do not mean offence, lord,’ da interrupted, seeing the rising anger in the warrior. ‘There is not enough room for you to sleep in the roundhouse, my apologies. The shed is warm, not overly fragrant, but warm. You may eat with us, then, I am sorry, you must retire.’

The warrior also surprised me when he said, ‘I thank you for your hospitality,’ before dismounting and rubbing the backs of his legs.

‘Is there somewhere I can water the horse?’

‘The ox shed is under the eaves, there,’ da pointed. ‘There is straw inside and a trough with water at the side. Do not startle the ox, it is a temperamental beast at the best of times. You boys go home. There is nothing to see here.’ Saying which, da returned to his chopping and the warrior walked his horse to the ox shed.

I nodded at Diarmuid as he backed away, before following the aging warrior, keeping my thoughts to myself. I did not want to be sent away. I wanted this man to tell me all about the life of the Five Kingdoms I had missed. I wanted him to tell me why he was carrying wounds. I wanted him to tell me what was in the leather sack slung over his mare’s neck. The sack that looked suspiciously round and seemed to have blood caked to its base.

When he reached the shed, the warrior put his clenched fists into the small of his back and stretched with a groan. His horse skittered as he took off her saddle. I could feel the oppression of the forest that was making her nervous. Wolves were howling. Mists were rising from the forest floor. The night was always a time that was best spent under the thatch of the roundhouse, beside the fire with the aromas of cooking and the safety of deep sunk timbers.

‘You feel it too, Dornoll?’ he asked, patting her neck and feeding her a handful of oats from his saddlebags. She tossed her head and neighed. I watched the warrior duck into the ox shed and reappear with two fistfuls of straw. He began to wipe down the mare’s flanks, lovingly, cooing as he did so.

I could not resist and asked, ‘What is in the sack?’

‘What do you want, boy?’ the warrior asked, without looking away from his work.

‘Nothing,’ I shrugged, unsure what to say.

‘Nothing, he says. Well then, get lost. I do not like children at the best of times, but nosey children annoy me.’

‘I am not a child,’ I said, knowing that compared to the old man grooming his horse, I was hardly a man. When he lifted the back of his hand, as if to give me a swipe, I ran, but only as far as the eaves from where I could see without being seen.

When he had finished wiping down his mare and had hobbled her beside the shed where she could reach the water trough, the warrior returned to our roundhouse and knocked on the upright at the entrance before lifting the oxhide cover.

‘Enter, warrior, be welcome at our table,’ I heard da say from within. Again, his tone did not lend credence to his words. I ran around the side nearest to the deer path and propped myself against the logs next to a small crack, where I knew I could hear without being seen.

‘What is your name?’ the warrior asked.

‘I am Tiubh, and she is my wife, Gránna.’

‘Where is the boy?’

I nearly laughed when I heard da say, ‘He is using the last of the light to finish his game. As he always does before nightfall. No controlling the brat.’

‘He asks a lot of questions.’

‘Yes. The curiosity of youth. Mead?’ There was a pause. I suppose da was pouring the sweet liquid. Perhaps they were both a little nervous in the company of strangers.

‘I heard rumours of an invasion,’ da said, after the awkward silence.

‘It has been quashed the invaders put to the sword. More,’ with a thump of flagon on the tabletop.

‘And the leader of the invasion?’

‘Is dead.’

‘What of the high king?’

‘What of the high king, the bull’s ball sack asks. I can see where the lad gets his curiosity.’

‘I did not mean offence, lord. As a farmer, I need to know I am safe to continue tilling the soil. I need to know if the Peaceful King is alive. I need to know whether I should take my family and hide in the forest.’

‘Are you not already hiding in the forest?’

‘I meant deeper in the forest.’

‘I know, I know,’ followed by another pause. I could see in my mind the warrior holding up a hand, a mixture of impatience and tact. ‘He died at the hands of Ingcél, the leader of the invasion. The Briton executed him after the battle at the hostel in Glencree. Put his head on a cairn and stole all the horses.’

I felt my heart quicken at the news. I had never seen the High King. Hiding in the mountains, we did not feel the effects of his time of peace. But we did listen to the occasional traveller who spoke of his generosity of spirit. He was known as the Peaceful King. To hear that he had died, seemed to be something of an omen to my young mind.

‘There was a battle at Da’s?’ I heard my father ask. He was familiar with the hostel in the valley of Glencree. He and the other men in the settlement would often ride the miles to drink and talk to strangers about what passed in the Five Kingdoms. Those were the times when I would hear my mother whimpering in the night in time with his animal grunting and would invariably get a beating the morning after.

‘Yes, the high king’s entourage were slaughtered defending him.’

‘What of Da Derga?’

‘Dead as far as I know. The hostel is in ruin. The gates nothing but blackened wood. If he lived, I am sure he would have repaired them by now.’

‘So, there will be an assembly to select a new high king?’

‘There will, but I do not expect any quick resolution. Conery’s only heir escaped before the battle at the hostel. No one knows where he is and there are no suitable replacements that I can think of.’

‘What of your king, Conchobar Mac Nessa?’

‘As I said, I can think of no suitable replacements.’

Da hesitated then. I knew he was dying to ask more about the possible replacements. I guessed the warrior was looking at da in the same way as when he had suggested the ox shed as a bedding place, because instead he asked, ‘Do you think an assembly of kings is a good place to make a start in life?’

‘Make a start in life?’

‘Where to begin seeking a fortune?’

‘What are you getting at, farmer?’

‘The winters are hard. My crops are not bountiful. My boy is growing too big to feed…’

‘So, you want me to take him to Tara, where he can make a start in life?’

I slapped the side of my head sure I had not heard correctly. Could da be trying to sell me into the slavery of this warrior? It seemed unlikely, but there was always a glimmer of hope in my young heart.

‘Yes, maybe you could find him a foster family?’

‘You really are a horse’s arse, farmer.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘He is a farmer’s son. Fostering is a privilege of kings, chieftains and warriors. What makes you think I can find someone to foster your boy?’ the warrior’s tone was incredulous. I sat there with my back against the timbers and my eyes screwed shut, willing the two men to say the right thing, the thing I had been longing to hear since the first time da beat me for getting in late from the forest.

‘But things have changed, lord. Since the arrival of High King Conery, the old and dated traditions have been replaced by more modern practices. I thought…’ da tailed off.

‘Ball sack, you did not think.’

‘I am sorry, lord. I only have the boy’s wellbeing in my heart…’

‘The boy’s wellbeing. You are trying my patience, farmer,’ the warrior interrupted.

‘Sorry, lord, I do not mean any offence.’

‘Boar’s arse does not mean offence, apparently. I will sleep on it. Now where is the food I was promised. I must eat and sleep. Tomorrow will be a long day, whatever I decide.’

It was obvious to my young mind that all talk was done. I stood up from my hiding place and walked into the roundhouse. I could feel the warrior staring at me as I leant my camán against the central pillar. There was a suppressed question in the intensity of the look. I remember making my face into a mask before turning to face him. I did not want my chance in life to fail because of any apparent eagerness. The old man did not return my look. Rather he sat staring into his cup of mead. I did not speak either but took the bowl of oats and venison from my ma and went out into the twilight to eat. I too had much to think about before the dawn.

The Reticent Detective – Trailer – Due for release in the autumn

The Love Nest

Laconto could not believe his luck as he stopped at the bedroom door and looked down on the near naked form of Welch. She was tangled in the top sheet, all that was needed in the balmy autumn nights, looking like she’d been wrestling a crocodile. Tray in hand, he moved to the window and looked through the half open venetians over the dusty rooves of the town of Baia. The noise of traffic fighting to get nowhere fast was yet to start, the air cool with the morning sirocco. From his vantage point, the inspector could see the island of Nisida and the volcano behind, taking shape in the growing light. Although he couldn’t see it, Laconto knew the city of Naples, nestled between the two, was beginning to waken.

Laconto was happy for the first time in a long while. After Ele, the soon to be ex-Mrs Laconto, the inspector had been convinced there would be no others; convinced that love had left him for good. He didn’t normally have the time for fraternization, being the Anti-Mafia Directorate Senior Investigator for the district of Pozzuoli. Nor did he want a repeat of the heart-wrenching separation, when he’d lost a wife, two sons, a positive bank balance, a villa and an Alpha Romeo.

To avoid a repeat, he’d decided to devote himself to his work. Not that he hadn’t already been devoting himself to his work, the reason Ele had filed for divorce. He’d missed the irony previously, because since the postman left a note telling him to go and collect the registered letter, he hadn’t been in the mood for reflective contemplation. Now, the irony caused him to smile wryly and look through the venetians again.

He thought about recent changes to his life as the apartment block opposite exploded in a wash of orange light. He looked back at the girl on the bed, one breast and one leg exposed by the Kese Gatame she had on the bedsheet. Welch of the American NIS, the Naval Investigative Service. She was a sbirro, a cop, just like him, and subject to the same unsociable hours Ele had hated and which had driven them apart as inexorably as the heat of a Neapolitan summer. Rachel was like something from a fairy tale for Laconto. In her early to mid-thirties, she was maybe a little older than him, vibrant, intelligent, driven like he used to be when he first started his crusade to rid the world of wrongdoers. He felt with Welch at his side, he would be able to concentrate on his fight against The Syndicate and not worry about how she was being affected by it.

He wasn’t ready to continue, though, not yet.

Barely a month had passed since his first major AMD case had ended in a bloodbath. The aftermath of that bloodbath had caused their romance to blossom, like they shared a secret, which was fuelling their burgeoning lust. She, an American, not only young, but also a feminist striving for the pinnacle of her chosen profession, the Directorship of the NIS. He a chauvinist in a service riddled with cops beholden to the very organizations he’d sworn to destroy.

It made him smile to think only a few weeks before he’d believed women had no place in the police and Welch had been a feminist with the goal of making it to the top of that elite fraternity, a place traditionally denied to women in any profession.

They’d been thrown together by a bloody murder after an American sailor had been shot over a little ill-advised adultery. When a hostage situation developed, Laconto had given himself up in exchange for the women being held.

He shook his head, trying to clear it of the near-death images. Welch and her team’s timely intervention with a tear gas cannister through the window had made the difference between living and dying; breaking glass and the hiss of gas giving him the time he needed to grab a gun from the nearest killer and shoot the other before he had time to react.

The bed springs creaked, and he looked over to see Welch had finally woken and was looking at him with a smile.

‘Those for me?’

Laconto looked down at the tray he was holding. Espresso, orange juice and a cornetto, an Italian croissant-like pastry. He nodded, feeling foolish. He’d never been much for domesticity and hoped going down to the bar next to the station would be considered the same as making her breakfast in bed, her last wish of the night before she’d fallen asleep, exhausted by their frenzied love making.

‘Yes, I went to the café for them. You were sleeping. I did not want to wake you. You were so like an angel.’

‘That’s so sweet, Bobbi, thank you.’ He smiled, unsure whether he was sweet for getting her breakfast or for calling her an angel.

He stayed beside the window, admiring the litheness of her tanned body in contrast to the fullness of her breasts. He again felt a surge of emotion and luck and lust. ‘Well, can I have them?’

‘Yes, sorry.’ He walked over to the bed and held out the tray like some sort of votive offering. She puffed up her pillows, sitting unconsciously with her torso uncovered and smiled as she took the proffered breakfast.

‘The café where we first met,’ she said with a smile.

‘No, no, we first met in your Admiral’s office.’

‘That doesn’t count,’ Welch smiled. ‘It was such a fleeting encounter.’

Laconto could see the smile in her eyes. She was, how did she call it? teasing him. Yes, that was it. ‘You are teasing me, I think.’

‘No, really. What makes you think that?’ The inspector was about to respond when he caught the glint again and realized she was still teasing him.

‘Yes. Ha, ha, very funny.’

‘If memory serves, the second time we met, you were standing over a sailor with a hole in his head and his face in a puddle of blood and beer. Every woman’s romantic fantasy.’

Laconto laughed and thought about it. An American sailor, Koswalski, had been executed in broad daylight because he’d decided to fraternize with the wife of a Syndicate soldier. Laconto remembered mutilated lips grinning up at him. The dead eyes and shattered Ray-Bans a direct result of a man unwilling to keep his cock to himself, an opinion the inspector had voiced openly. It was hardly a surprise that Welch and he had got off on the wrong foot. That investigation threw them together, tête-à-tête and it had taken the course of it for them to learn to trust one another. Not too surprising considering one was a chauvinist, the other a feminist and on sides of The Law who rarely, if ever, saw eye-to-eye.

‘Are you coming back to bed? There’s something I want to talk to you about.’

‘We have three days off. I thought we would go into Naples, or maybe we could drive down to Sorrento for lunch and on to Positano for dinner?’

Laconto could see Welch frowning down at her glass of orange juice. He knew he was coming across as needy, sounding frantic in his own ears, but he couldn’t help himself. He didn’t like the sound of the invitation. In his experience, although limited, when a woman said she had something to talk about, it invariably didn’t mean something pleasant. The last woman to use those words with him had been Ele, when she’d called to tell him she was leaving and taking the boys and the Alpha Romeo. The same day as the funeral service, he remembered. That night, at least.

His elation of a few moments before began to wane, replaced with a butterfly stomach and a need for the bathroom.

‘Yes, that sounds nice, but I need to talk to you first,’ Welch pouted.

And so here it comes, he thought. I knew it was too good to be for real. ‘I will sit sul letto, um…’

‘On the bed,’ Welch interrupted.

‘Yes. On the bed, but keep my clothes on, if that will not be a problem for you?’

Welch laughed, ‘Why, you think I can’t resist your ripped abs?’

‘Abs?’

Welch patted the muscle mass under her breasts and said, ‘Abdomen.’

‘Oh, I…’ Laconto started to stumble, causing an ejaculation of mirth.

‘I was joking, Bobbi. Sit,’ she said, patting the bed beside her. Laconto sat and swung his legs up, kicking off his flip-flops. ‘Are you sitting comfortably?’

‘What is it, Rachel? What do you want to ask me?’

‘Do you remember our first date, in that pub?’

‘It was only a few weeks ago. Of course, I remember. That strange pub in Monte di Procida that used to be a clothes’ shop. You pretended that you smoke and nearly coughed your lungs out.’

‘But apart from that embarrassing interlude, I asked you how you came to be SI for Pozzuoli and you said you were too preoccupied to tell me a shaggy dog story?’

Laconto nodded. He felt he now knew what was coming. It was not as bad as he’d feared, but he wasn’t sure he was quite ready for it. Looking backwards was something he’d managed to avoid for a long time and not something he wanted to contemplate, despite his psychologist’s best efforts.

‘You want me to tell you my life story?’

‘Well, not all of it. Just how you ended up as the SI.’

‘I am not sure I am ready to tell that story, Rachel.’

‘Well, at least tell me how you ended up as a boy in blue. You can tell me that much, surely?’

‘It is quite painful.’

‘How you became a cop, what do you locals call cops sbirri?’

‘Sbirri. Yes.’

‘How you became a sbirri is painful? How can that be?’

‘Sbirro. Sbirri is when there is more than one, cops.’

‘Sorry, Bobbi, I keep forgetting, “i” for plural.’

Laconto hesitated for several seconds before he answered. ‘My father owned a shop for selling meat in our village. How do you call a macellaio?’

‘A butcher.’

‘Yes. Butcher. The local Syndicate family demanded protection money. Only a small percentage of the takings they said, but they decided how much the takings were, and my father could not afford to pay. He was too debole, too weak, to stand up to them and the police were in their control. When they told him of the bad things they would do, he took his own life.’

‘Oh, God, Bobbi. I’m so sorry. I didn’t mean to pry.’

‘What does it mean, pry?’

‘Ask too many damn fool questions.’

‘You did, then, mean to pry. Ma, va bene. But it is alright. Perhaps it is time that I spoke about it. The police doctor, how do you call them, doctors for the thoughts, psicologi?’

‘Shrinks?’

‘Yes. The police shrink has been telling me I must talk about it or write it down.’

‘You need to get it out in the open to get some sort of closure. My shrink is always telling me the same thing.’

‘Yes. I need to do that. Why do you have a shrink? You seem to be so normal.’

‘Where I come from, it’s a fashion statement.’

‘Oh.’ Laconto did not think he understood how exposing the inner sanctum to a stranger could be considered fashionable, but then there were so many other aspects of this fascinating woman that he doubted he would ever understand.

‘So, what happened with your father?’

‘He shot himself in the cantina, the cellar. Ho fatto un promessa. I made a vow that I would join the police and stop it from happening to other people. I was so naive.’

Laconto sat with his legs on the bed looking at the crucifix hanging over the balcony doors. What he had not said to Welch, what he thought she would not have any interest in hearing, was he was the one who discovered the body in the cellar. When his mother reported her husband missing, the sbirri told her he’d probably run off with another woman. It was more than a week later when the smell was so strong that neither Laconto nor his mother were left in any doubt as to where Laconto senior was. His mother had said junior was the new man of the family and had to go down into the cellar to confirm what they already knew.

The inspector had been twelve years old.

He’d stood at the top of the cellar stairs and flipped the light switch to see his father sitting against the back wall with his lupara, his shotgun, between his knees and his brains splashed up the wall behind him. At the time Laconto had wondered how his father was able to find the wall where he was going to shoot himself in the dark, before he remembered the lights were on a timer and always went out after an hour. No one had ever needed to be in the cellar for longer. No one until his father, that is.

Laconto looked at Rachel and frowned.

He didn’t want to talk about it, regardless of how much the police doctor said he needed to. And not just because of the pain. He didn’t think anyone should be put through the horror of the smell and the mess of blood and other detritus up the rear wall, or the puddle of puke at the top of the stairs after he had regurgitated his breakfast. He certainly didn’t think sitting in bed with an exposed chest was an ideal location for a woman to hear all the gory details.

‘Anyway, I kept the promise and joined the police as soon as I was old enough. And that is how I come to be here, the AMD Senior Investigator for the district of Pozzuoli. The end. One hairy hound story less to worry about.’

‘Is that it?

‘Yes. There’s not much more to tell, really.’

‘I read your jacket, Bobbi. I must admit, I didn’t believe it at the time, but apparently, you’re the best anti-Mafia detective in the province of Naples, if not Campania. There must be more to it than that.’

‘You want more?’

‘I want the whole sordid story, and you’ll not get away from me until I have it,’ Welch laughed and put her head on his chest.

‘I better make sure it is the hairiest of hairy hound stories then,’ he said, hoping the tremor in his voice was evident only to him.

‘Yes, you had, and it’s shaggy dog.’

‘What is the difference?’

Welch shrugged. There was no difference, but hairy hound just didn’t sit right.

‘Where shall I start?’

‘Why don’t you start when you became a cop.’

‘Oh. Okay, then. It started when I graduated from the Naples State Police Academy in seventy-five…’

Conaire Available for Free Download

From the first of June, Conaire will be available for free download for a limited time from: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B075X33W6F

The Reticent Detective Synopsis

Due for release in the autumn:

“We are all outside the law, just some of us are further out than others.”

Laconto is a police inspector with a past he does not want to discuss. He’d graduated the academy with ideals buoyed by innocence, only to have them crushed by policing a quasi-dystopian state, ruled by gangsters.

Like Laconto, Welch is a cop, but she is also a listener. She encourages the inspector to break down his walls. Beguiled by her charms, Laconto recounts his journey from fledgling with a dream of crushing organized crime, to Senior Investigator in the Anti-Mafia Directorate. Welch hears about a transvestite mugger, his lover, and two bent cops, all being manipulated by an unscrupulous Agent.

Gigi, dealt a heavy hand, rebels against the institutions there to nurture him. He turns to petty crime, which leads to a term in a Detention Centre, where he meets and falls in love with a like-minded boy. They become soulmates. Back on the outside, they cross a local boss and young love is torn apart by murder and a return to prison.

Subdolo and Colino are on the payroll of the local Mafia. They have no scruples and see Laconto as a threat to their status quo. What begins as a crusade to keep the recruit out of their business, ends in the tragic death of Laconto’s stepfather.

Spione is on a mission. An agent on the Secret Service Mafia desk, he wants to crush organized crime. Unlike Laconto, Spione will do anything to achieve his goals. He conducts a sting operation that fails and brings him face-to-face with the detective. Convinced that Laconto is bent, and the cause of the failure, he sets out to destroy him.

Living the Life

I have often been asked why I write about organized crime and corruption in Southern Italy. What could I possibly know about it? I admit, I am no Roberto Saviano, however, I lived in a village north of Naples for thirteen years. I saw first hand the life the locals led, governed by La Camorra, who provided work as well as protection. I was there when Berlusconi was arrested outside Castel Uvo by the Carabinieiri. I watched them lower his head into the back of an Alpha Romeo from the steps to the BA offices where I was buying tickets. I was present at a punishment shooting where an unauthorized petty-criminal was knee capped outside my local bar. I was asked by the local boss to go out on a Zodiac in the middle of the night to collect contraband off a Russian freighter.

Much of the material in my books is based on events that I witnessed first hand. The next instalment, The Reticent Detective, tells the story of an idealistic detective who wants to right the wrongs. It is currently at various publishers, but whatever happens, will be published in the autumn.

Son of Light: Taster

Son of Light

They call me Son of Light because Lugh, the God of light and the sun, is said to be my father. Most say it with respect. Those who think it was a ruse say it with a sneer, but never to my face. No one has had the courage since the festival of Samhain. Not even King Conor, who sneers at everyone except his druid, Cathbadh.

I hear you, though. How can a demigod be half dead and tied to a rock, your silence screams? You think I do not know the truth of it? Of course, I know. It was a ruse of King Conor, obvious to me because my father had been a bent-backed farmer and the only thing light about him had been his respect for my mother and his courage. I was not born on the plain of Murthemney, son of the king’s absent sister, Deichtine and Lugh. I was born in the Wicklow mountains, son of a wife beater and a drunk.

My sight is blurred by pain, but still I see Laeg, lying where he fell, after you cowards jumped out from behind your bushes and your rocks and pierced us with your javelins and your arrows. Laeg was a man I loved. A man who followed the code and died because of it. A man who was more than brother to me. There lies a man of courage with a javelin in his side and an arrow in his eye. He waits for me in the mound of Donn and wonders at my delay.

I wonder should I be talking of courage when I look at you so-called warriors of Connacht, sitting there with your swords across your knees, afraid to approach a mortally wounded man who is tied to a rock. True, my reputation is fearsome, but now the night approaches and the ravens prepare for the feast, I cannot lift my shield arm, much less parry a lance thrust. I am so weak, wearied and pained, I long for the night. I long for that never-ending sleep.

Does that give you courage? No. Still you sit there and watch, waiting for my end. I can see now why you serve the witch. She too does not have the courage demanded by her station. The Warrior Queen who sends girls trained in witchcraft to do her deeds and hides behind bushes and rocks when killing is required. But then, small wonder, because she is married to a sot; the drunk who was once a king, once your king.

What, not even insults to your king and queen will cause your ire to rise? You are more than just cowards. You are turds, as well. You squat there, behind your fires, quaking and I would wager most of you do not know why. I would wager your knowledge comes from the bards who could not tell the truth if their lives depended on it. Those who claimed Dond Desa had arse cheeks like two rounds of cheese and killed a hundred men with one stroke of his war hammer. Pah. Those who claimed Ingcél, when he landed his war fleet, made so much noise the Five Kingdoms shook. Those who claimed Macc Cecht’s knees were so hairy they looked like bowed heads and he killed six hundred with the first stroke of his sword. Those who say I killed my first warrior when I had seen but seven festivals of Lughnasad and the only way to appease me was giving me the teats of the settlement mothers to suckle on. Pah. When I was seven, I could barely lift a camán, let alone stab a man with a spear.

You do not need to kowtow to your ignorance, though. If you have the courage to listen, I will tell you the truth of it on this, my dying day. What am I saying? I do not care if you Fomorian spawned turds have the courage. I will tell you anyway. And you will listen, because the only thing that scares you more than a half-dead hero, is the wrath of your ill-gotten warrior queen. She has ordered you to see me dead, so sit and wait and watch you will. But you will also listen. You will not be able to prevent yourselves.

Son of Light Available to Pre-Order

Son of Light is available to pre-order from:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B07QH1JY48

Cuchulainn, the hero of Ulster, known as The Hound of Cullen as well as The Son of Light, is mortally wounded. He has tied himself to a rock so he can die on his feet with his sword in his hand. His enemies surround him, but are too wary of his reputation to approach. Weary from two days standing at the rock and pained beyond endurance, The Hound tries to goad his enemies into killing him and allowing him to enter the night.