Interview questions for @JohnDeBurca our #debut #author. 5 days. 5 questions.

- “What inspired you to write The Last Five Swords?”

Publishing Services

Interview questions for @JohnDeBurca our #debut #author. 5 days. 5 questions.

John lives on the mysterious and rugged shores of the West of Ireland in Galway. From a young age, John was immersed in the rich traditions of Irish oral language storytelling, amassing a vast collection of mythology and folklore. He joined a storytelling group when he could find one and started to hone his skills.

John’s debut novel, The Last Five Swords, is an epic fantasy adventure set in a dark and beautiful ancient Ireland. It will be published by PerchedCrowPress in the Autumn.

| When Eoghan and Rúadhan find a girl up a tree, it heralds an epic journey. Rhíona is a Fae princess on a quest to find a hero. She is hunted by her father and his agents, ambassadors and assassins, all set on thwarting her plan. They soon fall in with Donnacha, an archer with a secret. Together, the four enlist the help of the last of the fénnid. A world-weary group, far removed from the legends described in fireside stories. In the dying days of magic in Ireland, the motley band sets out to find the greatest champion ever known: a man long thought dead. There is no other choice because only Fionn Mac Cumhal can save Ireland one last time. “Wonderful Irish fantasy storytelling by debut author, John de Burca” — Conor Kostick, international bestselling author of Epic. Buy the book |

| Eimear was born to the sound of violence. Her parents broke the ancient geis and fell in love, despite coming from different races. Murdered on the day Eimear is born, a knowing infant, their legacy is one of pain and loneliness. Although watched over by the duillecháns, Eimear’s childhood is unforgiving. She moves from one evil guardian to the next, that is, until she finds Sword and discovers its music. Sword’s discovery starts her on an epic adventure across multiple worlds–a journey of self-discovery and an introduction to further horrors. Eimear’s journey brings her into the world of the Fae, where a bottomless crease divides the worlds of the Fane and the Fand–the King and Queen. The King and Queen want to use Eimear to unite their world and begin a reign of conquest and subjugation where no world is safe. Unaware that they are being manipulated, they march on blindly towards their destruction. Buy the book |

Battle of Watling Street. 60/61 CE. Heavily outnumbered, the Romans prevailed. Boudica blocked retreat with spectators. Maybe as many as 80k killed. The Romans were said to have lost only 400.

Hammer: coming in Autumn.

For a limited time, both books for £3.99. That’s a saving of £5.

Love, murder, corruption and misogyny under the volcano.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B08N6SJ34X?ref_=dbs_p_mng_rwt_ser_shvlr&storeType=ebooks

Charcoal sketch of Baia Terme station (now closed) where PO Jones was shot in ‘79. The Alcoholic Mercenary on special tomorrow.

“…this book was utterly compelling from beginning to end” — Book Bandit’s Library

Writing the battle of Menai Straits.

Druidesses cause the XIV Legion to halt their crossing through fear. Agricola will lift them to a resounding victory.

Hammer: coming in the Autumn.

One question I am frequently asked is, “where do you get your inspiration?” or couched slightly different, “why was I drawn to write about Naples?”

I suppose answering those types of questions will be different for each writer. I have knocked together a couple of responses I gave during the recent blog tour of The Alcoholic Mercenary.

I spent my career working as a writer and editor. When a contract came up in Naples, I had been in a three-month lull, so I jumped at the opportunity. I was not so much drawn to Naples as thrust into the furnace by an accident of fate. The city was dirty, corrupt, and overrun with criminality, and I loved it. More of a surprise: my wife loved it too. In fact, we loved it so much that we lived there for many happy years.

Having been a writer for so long, writing about a location of such contradictions was out of my control: I could not resist. By contradictions, I mean such things as it being one of the most OC-infested areas of the world, yet the local people are some of the kindest (including the criminals). Core d’oro, the locals call it, or heart of gold. For instance, when we arrived, a gangster invited us to his sister’s wedding, which turned out to be the opening scene of The Godfather, even down to the local folk music and strange dancing. I am sure, somewhere on the grounds of the sprawling restaurant, a Don was conducting business as we dined on a sixteen-course dinner.

The Alcoholic Mercenary is mainly based in Pozzuoli, the primary urban centre (or commune) where my wife and I lived. We lived in a fishing village called Lucrino, on the outskirts of the Commune di Pozzuoli, a few kilometres up the coast. In the photo, Lucrino is the village crawling up the dormant volcano, Monte Nuovo. I took the photo from the restaurant where the gangster’s wedding was taking place.

Unlike in Northern European countries, the criminality in Naples is not bound by education necessarily: at the bottom end of the spectrum, the uneducated, unemployed masses, who, by the very nature of their society, turned to the mafia to make a living (I use the past tense because I am not sure if it is still the case) versus the educated few, who stuck their noses up, those with a puzzo sotto il naso — or a stink under their noses. A good education is available to those with money and not necessarily brains. Being taught to know better does not preclude Neapolitans from the criminal class. As an example, we had a friend who was a doctor. He was involved in an OC scam, where disability certificates were sold. He was quickly caught because he sold a certificate of blindness to a guy who was subsequently arrested for speeding up the motorway. After being stopped, the police discovered he was without a license, tax, or insurance and — it later transpired — without the use of his eyes. How anyone so intellectually challenged became a doctor should be a mystery. It’s not because it’s possible to resit your exams in Italy until you pass (as long as you can afford it). Our friend didn’t graduate until he was forty-two.

One of my many anecdotes about the contradictions of Naples involves another friend asking me to help him find his Persian Grey. I agreed. He told me the cat had gone missing in his local area, and we stopped by his house to run an “errand” before beginning the search. The errand turned out to be his retrieving a Colt .45 from a shoebox under his bed. Searching involved knocking on his neighbours’ doors and demanding the return of his cat with the Colt visibly protruding from the waistband of his chinos. We never found the cat. My friend confessed to asking for my help because, at 6’2, the locals considered my height sufficiently threatening that the Colt never needed to be drawn. Only believable when you learn that in Naples back in the nineties, the average height of men was 5’4. The contradiction of searching for a fluffy feline with — what was really — a cannon stuffed in his chinos never fails to astound me.

Of course, as a historical fiction author, research is paramount. Researching The Alcoholic Mercenary’s locations is probably the most problem-free of my projects to date. As I wrote earlier, I lived in the Commune di Pozzuoli for many years and know it very well. I suspect Pozzuoli has changed very little, despite returning to Ireland in 2006. I first visited the town in 1975 while on a month’s holiday. When I returned to live there in the early nineties, the first thing that struck me was how it had remained fundamentally unchanged. The whole area is known to live in a time warp. For instance, the local economy is barter-based because of a lack of employment. The doctor mentioned earlier was paid for home visits with local produce: half a pig or a demijohn of wine, to name but two.

Other areas I describe in the book include the airport at Capodichino and Bagnoli NATO base. I flew in and out of Capodichino on countless occasions. In fact, the scene where Rachel arrives on the apron to feel the heat through her shoe soles is based on my own arrival. I also used to teach Shakespeare to the children of serving US Navy and Jarheads at the high School on Bagnoli NATO base. As such, I witnessed the rundown nature of the interior firsthand. I also bought stuff in the PX on the base, possible because of Mary, my next-door neighbour’s, goodwill. Mary was a US Navy meteorologist based at Capodichino Naval Support Activity command.

I did use a well-known map app as a pro-memoria to street layouts, but that was all.

Another question that arose out of the blog tour was how I used my experiences as inspiration for The Alcoholic Mercenary.

Over the years, I had many experiences: from being asked by the local boss to go out in a Zodiac as a smuggler to owing a favour because a mafioso returned my stolen motorbike. I could write about the execution of two informants in the foyer of a neighbouring apartment block (palazzo) or eating in the restaurant where Maradona allegedly bought his cocaine. Or I could write about a friend’s father committing suicide when the local clan kept burning down his tailor shop because he wouldn’t pay for protection.

For the sake of this article, I shall restrict it to one story told directly in The Alcoholic Mercenary.

An aspect of Organised Crime that is common throughout the world: from various mafias and tongs to the IRA, is the concept of punishment. Any unauthorised crime tends to be dealt with swiftly and brutally. This is no different in Naples.

While we lived in Lucrino, there was a heroin addict who was known to do a bit of selling on the side. He bought his supplies from African drug dealers operating in the city’s hinterlands. They sold their drugs in cul de sacs laid out where no houses were ever built (also in the book). I know this because my bike broke down outside Lago Patria, and he offered to tow it back for me, but he had to run an errand first. The errand ended up being a cat and mouse chase around empty streets (and by empty, I mean streets without houses) with a car full of African drug dealers. In all my experiences, this was the scariest. The drug dealers in their Fiat Punto (four of them) were definitely armed and not affiliated because in Naples in the nineties, racism was rife. No one would deal with the Mau Mau (a derogatory term for African criminals). Affiliation was vital because it meant some form of control: a set of rules, if you will. The car chase ended up in a houseless cul de sac. After which, it involved exchanging a small fortune (payment for the tow) for a condom full of heroin that the dealer had tucked away in the side of his mouth.

The guy who offered a tow was skinny and always wore an open shirt and a grimy vest. He had a greasy ponytail and a broken-down Fiat 500.

Apparently, his drug dealing was unauthorised because he was kneecapped outside our local bar one Saturday morning while drinking an espresso. Its audacity would seem astounding, except no one would act as a witness, not even the victim. After his punishment, I only saw the dealer once more, hobbling down the street with a removable cast on his leg and crutches. I can only assume he either moved away after that or failed to heed the warning.

This episode is told in The Alcoholic Mercenary when Boccone kneecaps an “unauthorised” drug dealer along the seafront of Pozzuoli.

Another question on the blog tour was what inspired me to write The Alcoholic Mercenary (as opposed to which experiences), such as outside influences, other authors and so on.

I always struggle when asked what the inspiration is behind my latest book. How far back do I need to go? Should I write about my favourite authors, personal experiences, passion for creative writing and all its figaries? Or should I just write that living in the village of Lucrino drove me to write books based there?

For me, a passion for writing begins with a passion for reading. The inspiration behind any book — be it the first or the last — must start with that passion. I remember reading The Lord of the Rings while bedbound with the mumps. I read the book in a week and began my first scribblings after putting it down. I was twelve. Of course, reading Epic Fantasy nearly fifty years ago has little direct bearing on The Alcoholic Mercenary. Still, it did mean I now have the tools to write, which I probably would not have otherwise had.

Authors directly influencing TAM could include James Ellroy (for his Noir writing style) and Andrea Camilleri (for his tongue-in-cheek portrayal of Southern Italian law enforcement). There are, however, many more writers who have inspired me over the years. I must have read thousands of books since I put down LOTR. My reading tastes are not bound by genre. I could list every author I read if the article was not set at a particular word count. Still, it is, so I will condense the spectrum: I read Stephen King’s Carrie during the seventies in one night while babysitting, and, in contrast, I read Twelve Caesars by Suetonius over several days while researching a historical novel set in pre-Christian Ireland. Why? Because the Roman historian Tacitus claimed Agricola invaded Ireland while governor of Britain. That claim is the premise for a trilogy I am currently working on.

So, what inspired me to write TAM?

I touched briefly on my time living in the village of Lucrino. My wife and I lived next door to a meteorologist in the US Navy, Mary, and her husband and child. Many more US Navy rankers were residing in the area. Because we spoke Italian and tried to fit in, we were accepted into the local community. The Americans were not. Our neighbour’s car was broken into every night until they stopped locking it and left nothing of value in it.

On the other hand, we would go out, leaving all the windows open and not burgled once. That said, my motorbike was stolen one night, but a “friend” returned it the following day with notice of a favour owed. In the nineteen-eighties, that friend had been hauled off to the merchant navy by his older brother because he was the bodyguard of an intended murder target.

So, we have the ingredients that inspired me to write TAM: a young man in trouble, saved by an older brother; a woman in the US Navy thrown into the cauldron; a place of contrasts and conflicts. And finally, while we were living there (and Schengen had not been introduced), we had to report to a Police Inspector to get our visas renewed. The inspector in question was a well-dressed Franco Nero lookalike — inspiration for Bobbi Laconto, my version of Montalbano.

Whenever I get revisions back from my editor, her cover letter says something like, “Overall, Phil, I think the plot of The Alcoholic Mercenary is excellent – you’ve brought in all the key elements of the noir genre, combined them with tight writing…” (actual). In this instance, Georgia noted my “tight writing”. The tightness is not because I’m excellent at my job— a wordsmith like Winnie used to be— but because of the editing processes I follow. This issue of the blog describes those processes.

INTRODUCTION

Editing is by far the longest blog in A Technical Approach to Novel Writing. That is no accident. Editing a manuscript is the most difficult — and important — part of the novel-writing process, regardless of what approach is used to actually write. Quality is key. Once again, my opinion flies in the face of Stephen King’s adage that readers don’t care about quality, only about the story. I would argue that Mr King’s theory depends on the reader more than anything.

| Take The Thursday Murder Club as an example. At the time of writing, there are ~100k reviews on Amazon. 64% are five-star and 3% are one-star, and a further 3% are two-star. Reading the one and two-star ratings, a common theme is the poor quality of the book. Admittedly, it is a multi-million selling phenomenon, which obviously supports MrKing’s theory, except — in my opinion — the story is not particularly good, either. I believe The Thursday Murder Club sold because of the celebrity status of the author, not because readers don’t care about quality. |

Today, it doesn’t really matter whether a writer intends self-publishing or to go down the traditional route, as far as I am concerned, it is still necessary to edit. Maybe it is my previous career talking, but I want my books to be the best they can possibly be, regardless of what my readers want. I can take negative reviews on the chin — though not very well, they hurt — but if they refer to poor quality work, then I have failed.

So, Who Pays the Ferryman?

The publishing world has changed where book quality is concerned. Gone are the days when publishers would foot the bill. In today’s market, they can’t afford to and expect an MS to be as near perfect as possible when it is submitted. Similarly, if an editor receives a manuscript that is not up to a certain standard, they are likely to refuse it. It is not an editor’s job to rewrite a poorly written book. A marked deterioration in the quality of books from an editorial perspective is not an accident. I heard that publishing houses have switched the onus onto writers. It is now not uncommon to find a glut of typos and grammatical errors in books released into the market, even by reputable publishers like Penguin — never mind the redundancy developmental and line edits would have removed. There has also been an explosion of purple prose, no doubt because self-editors believe flowery and ornate passages constitute good writing and there is no one there to correct them.

I suspect this fall in quality is because writers — given the choice of either paying the publisher to edit or doing it themselves — will do their own editing. “If I can write, then I can edit”, I imagine to be something said quite regularly in the writing community. This might well be true to a large extent, only not the writer’s own work. A common human trait is to read what is expected and not what is present. This becomes triplicated when auto-editing. I was an editor by trade but I will always have my books at least line-edited and proofread by autonomous professionals.

So, there it is, I pay to have my books edited. Sounds a bit like a baker going to the local supermarket to buy bread, but it is the reality of the world I inhabit. That said, it is still important to have my MSs as near perfect as possible before I submit them to my editor, so I employ a complex editing process.

What do I Watch For?

The obvious answer is typos and grammatical errors. However, a good edit goes a lot deeper than that.

I suppose — like everything I do as a novelist — how I edit is heavily influenced by years in the technical documentation arena. From a wet-behind-the-ears specification writer to a senior manager in a global SW company the key was always the same: getting the message across. I don’t believe the key should change just because the arena I am in is now creative instead of technical.

Editing in the technical world is based on style guides, such as the Chicago Manual of Style, The IBM Style Guide, and the Microsoft Style Guide, as well as internal guides. In my later career, as an editor, writing internal style guides was my responsibility. The last style guide I wrote couched terms like clarity and brevity, redundancy, accuracy, consistency, and navigability. These are all terms that can be — to a greater or lesser extent — applied when writing a novel.

Clarity, Brevity, and Redundancy

The writing should be clear and precise. When reading, I hate having to reread sentences because they are unclear. It detracts from the reading experience and slows down the story.

In terms of brevity, I do not write sentences of thirty words when twenty would do the trick (never allowing that guideline to affect pacing — if I want to slow it down, I write longer sentences). In On Writing, Stephen King says cut, cut, cut, and cut again (paraphrasing). I would hate to think how big The Stand was before the cutting commenced, but he’s not wrong. So, what is it I cut?

Personally, I am guilty of repeating messages worded slightly differently. This is redundancy. My editor actually finds most of these, but I do try before I submit the manuscript. The various audio edits help this (see the following). Redundancy is a major headache for documentation in the IT industry. Someone who has just bought an enterprise-level software platform doesn’t care about the team’s brilliance when developing it. They want to know what the story is. In today’s reading world, this is also true. Readers don’t care about all that flowery exposition writers tend to think is indicative of good writing. They want a story they can lose themselves in, not a story they have to dig out from a purple flowerbed.

On top of my redundancies, there are, of course, the redundancies created by adverbs and adjectives. The King wrote, “the road to hell is paved with adverbs” Although guilty of breaking his own guideline, once again, he is not wrong.

Accuracy

Accuracy is key for me. Whenever I read a novel with inaccurate statements it turns me off. It is not only historical novels that require research. I recently reviewed an epic fantasy novel, where during training the sword master instructed his pupil to watch the feet of an adversary. Advice that would result in immediate death in a battle scenario. A little research (or a line edit) would have prevented that error. Another inaccuracy was in Patriot Games where Clancy had Queen Elizabeth commanding the Prime Minister, which, of course, does not fit with the British political reality. Only a little research would have prevented that faux pas.

Consistency

It is important to be consistent. I reviewed a novel recently where the author switched between metric and imperial throughout the story. This immediately made me aware that a professional line edit hadn’t been done, or if it had, hadn’t been done well. Consistency also refers to characters. They should be consistent except when breaking consistency is an intentional plot device. If your main character enjoys farting after eating, they should do so throughout the story.

Navigability

Navigability is — in today’s world — the least important aspect of novel writing. It comes down to a table of contents because indexes are not usually present in novels. However, with TAM — because it is set in Italy, and includes Italian slang, I included a glossary. For the electronic version, it was necessary to convert the glossary into footnotes so readers can easily access definitions with a minimum of distraction from the story (enhanced navigability). Some might say glossaries are not commensurate to a flowing story, but neither is confusing a reader. I have received five-star reviews because I included a glossary.

Overused Words and Literary Devices

I am yet to meet an author who doesn’t overuse something in their writing. One of my favourites is “look” and its variations (looked, looking, looks). During the final editing phase of After Gairech (2021), my editor found 411 variations of look in a book of 90k words (350 pages), sometimes, several on the same page. Too many. This type of overuse is easily fixed. As well as using alternative words, I fix individual repetition with methods that don’t require a thesaurus, such as restructuring places where they occur. For example, I find I often use “look” in dialogue tagging, which many experts would frown on anyway. With a restructure, I remove the tagging and the “look”.

It is not only words I watch out for. Another irritating habit is the overuse of similes and other literary devices. I recently reviewed an ARC of fewer than 300 pages (real: Amazon cited a print length of 320 pages, but many of those pages constituted front and back matter, as well as white space) that had 311 occurrences of like, most of which were similes (I didn’t bother researching the as similes because 311 is already high). Reading it was like being beaten over the head with a half-inflated sumo suit (pun intended). It was as though the author thought simile to be indicative of good writing. Perhaps, in some other hands, it might have been, but not only did the author overuse them, but they also did it extremely badly, “…like a hedgehog that has wrapped itself in paper beside the bins to keep warm”, being one example, where the author was describing wrapping on a present. With a lack of opposing thumbs, or intellect, I would defy a hedgehog to wrap itself in anything. Not only is this a bad simile, but it could also be classed as purple and redundant.

So, before I send a manuscript to my editor, I do a trawl of overused words and devices, metaphor and simile in particular. When I find metaphors and similes I make sure they work and if there are too many, I rework some of the occurrences. When I find words repeated several times on a page, I do a search to make sure there are not too many occurrences throughout the book, and not only on the page in question.

Show, Don’t Tell

To some degree, the creative writing world is filling out with the same level of jargon that has been plaguing the technical world for years. When I see sweeping generalisations like “show, don’t tell” I want to pull my hair out by the roots (I probably would if I had any). I challenge any writer to write a book without any telling in it. Just as I challenge any reader to enjoy a book without any telling in it. Where is the cut-off from showing before it becomes plain old purple prose? I am sure I don’t know, and the more I read about the subject, I am sure I’m not alone. What Chekhov is alleged to have said was, “Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass,” which is paraphrasing something he wrote to his brother, but gets the gist. Most so-called expert definitions I have read simply use it as a license to advise writing purple prose, missing the point entirely. One I have often read in different guises being, “If your manuscript is short, make sure you are showing and not telling…”, which I would reword to “…make sure there is a balance between showing and telling.” I saw a question from a writer recently that said how do I show that the house is red? If I had responded to the question — it wasn’t directed at me — I would have countered with, “does the house colour matter”, but that’s a slightly different question. The real answer would be, “you can’t”. The show, don’t tell advocates, would propose varying levels of exposition, but eventually a variation of the statement, “it’s red” would need to appear.

Showing versus telling is, of course, something that requires balance. If a writer wants fast-paced edginess at some point in their story, they are likely to lean towards telling mode. Exposition skirting speedy events (such as a chase) can lessen the impact. On the same token, wham bam thank you, mam, is unlikely to increase sales of a romantic novel. The emotion needs to be evident.

| Is wham bam thank you mam showing or telling? Discuss. |

What’s My Process

When a writer thinks about editing their work, if they are a newbie, they might picture a stack of A4 sheets and a red pen. They might imagine a process of (for want of a better cliche) crossing eyes and dotting teas (error intended). However, editing a novel — and indeed most other documents — is a complex process done throughout the document’s lifecycle, which includes a lot more.

I’ve read many different interpretations of the editing process. Some I agree with, others, not so much. The following are the editorial stages I use during the production of a novel:

| I have often heard new writers ask, “When will I know if my book is ready?” As far as I am concerned, it is ready when the steps in this list have been completed. |

I will describe each of them in this blog issue, and explain the benefits I derive from them.

Developmental Edit

Essentially, in my process, dev editing is testing the story arc of a novel, which means filling gaps and removing redundancy, as well as testing timelines. Officially, dev edits would cover things like character development and dialogue as well as story arc, but I cover that aspect in the second dev edit phase because I perform this edit on my scene plan.

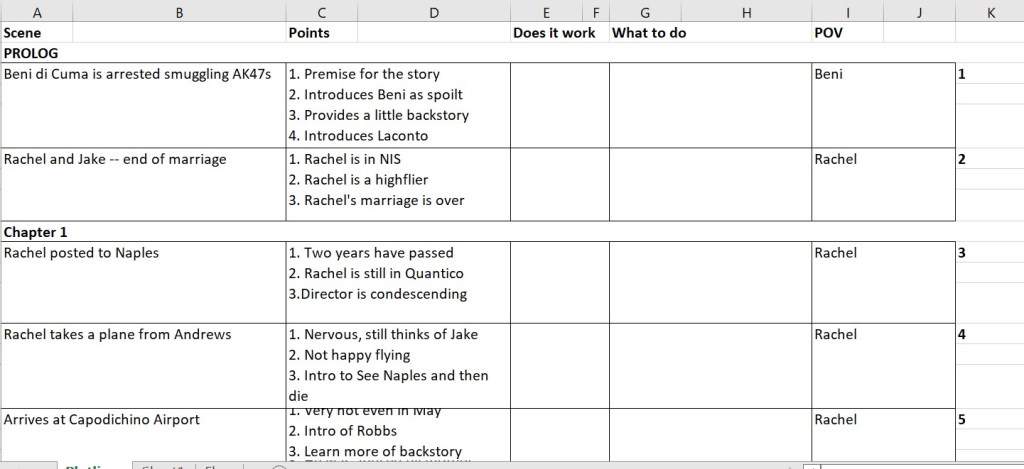

As mentioned in my previous post, I keep a spreadsheet of scenes, which is numbered and includes things like actors, POV, plot points, and status. On average, a crime novel should be around 80 to 90k words. For me, a scene usually ends up between 800 and 1000 words and so I aim for around 100 scenes in my arc. This is not something set in stone. For example, an earlier novel I wrote (The Reticent Detective, 2019) had 120 scenes in the original arc, many of which were cut before I went to print.

The following is an excerpt from the structure of The Alcoholic Mercenary (TAM).

There are several columns.

Scene: A brief description of the scene. It doesn’t need to be elaborate, just a pro-memoria.

Plot points: What the scene contains in terms of moving the story forward. Some schools would say each scene needs a minimum of three plot points, but I don’t agree. As long as a scene moves the story on, it can have as many or as few as required. In this regard I use three CCCs: change, causality, and conflict:

So, when I edit a scene, I make sure it contains at least one of the elements— thereby moving the story forwards. If not, I’ll either modify it or cut it.

Working Y/N: I leave this column blank until I get to the second dev edit stage. It is an indication of whether the scene is contributing successfully to the arc. Writers must be ruthless here. Sometimes it is hard to admit that a scene is not up to standard. In the writing community, this is known as “killing your babies”.

What to do: When the answer to the previous column is no, what action needs to be taken. Actions can include rewrites, deletion, the addition of a new scene, and so on. It is very important to be objective during this process. If a scene doesn’t belong, get rid of it (don’t throw it away, keep an outtakes file). Things to look out for are info dumps, padding — which means writing to reach a word count target — (I read a book recently where the author spent a whole chapter describing a retirement village, a pure info dump and redundant. A good edit of the MS would have removed it.), throat clearing.

POV: This column reminds me of which character has the point of view in each scene. From an editorial perspective, this helps to pinpoint issues with POV hopping. If you read Dune, you will notice Mr Herbert constantly hops between POVs within a scene. Since Dune was written, things have changed, and it is no longer acceptable to hop points of view in that way. Don’t get me wrong, Dune is still a fantastic book, and I would give it 5 stars all day long. Of course, an omniscient narration does not face this issue. However, omniscience is not the flavour of the day for modern readers. Similarly, first-person narratives do not face the issue.

| Remember, I don’t wait until my scene plan is complete before I start writing. |

Daily Edit

Each morning, before I pick up my quill, I edit what I wrote the previous day. This is a sort of copy edit, looking for typos and grammar errors. It is important that a writer refrains from doing this while writing because it will distract them and they could end up in a loop. If the writer does not have any editing experience, there are lots of apps out there to help this process. I won’t list any here, because a Google search would be more efficient. These apps cannot replace the formal copy edit that takes place after the first draft is complete.

| I don’t spend an inordinate amount of time on this editing phase. In-depth copy editing takes place at different stages in the book’s lifecycle. I basically use this edit to make the professional editor’s job easier. |

First Draft Read Through

This read-through is where I wear the hat of a reader. It is important to have gained distance from the manuscript before reading it. When I finish the first draft, I print it and then leave it in a drawer for at least three weeks before starting the read-through. When reading, I do not stop to make notes or edit. If something glares at me, I stick a coloured index marker to the page and carry on reading. After I finish reading, I go back and mark up where I left the markers.

Second Developmental Edit

I do the second developmental edit after the completion of my first draft read-through. I complete the scene spreadsheet with the Working y/n and What to do columns. This constitutes the first draft rewrite. Because I run a developmental edit on my story arc, I find this edit is more of a formality than anything. However, I usually remove several scenes as a result of this editing phase. I also, occasionally, add scenes. For TAM, I actually removed an entire chapter that was more throat-clearing than anything.

Audio Edit

Self-editing is prone to failure because when a writer reads a passage they wrote, it is common to read what they think should be there, rather than what is there. I catch myself doing this all the time. Many will say “read your work aloud”, which is sound advice, as far as it goes. For me though, it doesn’t work. I still miss syntactic and repetition errors. I guess that the same rule applies to line edits: I read what I think should be written, rather than what is written. So, is there a solution? I suppose the logical answer is to have someone else read. But won’t the same issue apply? Yes, if the reader is human. If the reader is an app, then no. Apps will only ever read what is on the page. They might get the pronunciation wrong and most of them sound robotic, but they do the job.

I use two forms of audio editing: during the writing of the first draft I audio edit each Google Doc before I paste them into my skeleton, and I do a full MS audio read-through and edit as part of the rewrite process.

| I think an audio edit is probably a writer’s best friend. I find a great many of the issues in my novels during a read-aloud edit. Especially things spellcheckers wouldn’t catch (that instead of than, for instance) and issues with repetition. |

For the full audio read-through, I create a PDF file with all extraneous text stripped out: front and back matter, as well as header and footer text (page numbers in particular). In this way, the PDF reader in Edge only reads the story.

I read along with the screen reader (in my head). This helps me to maintain concentration. I find a screen reader that highlights the word being read is the best sort. When I spot any errors (for both audio edits), I stop the reader and fix the issue, before continuing.

External Edits

I leave the line edit, copy edit, and proofreading to my editor. Because I have plotted the full arc and my work plan has informed me of when this is going to happen, I can plan accordingly. During the external editing phase, I work on something else (usually the garden, eight raised beds and a polytunnel take work).

I know when my MS comes back, it is going to be a mass of red lines and questions. This doesn’t depress me because I am aware of my limitations when editing my own work. My editor invariably starts the cover letter with very positive feedback before tearing me a new one through the manuscript. Rather than depress me, it gives me confidence in her because I know she is doing a great job herself. I would be suspicious of edited works which came back with few comments.

| It is important not to just implement the editor’s comments wholesale. I always read and analyse Georgia’s comments before I do the updates. Sometimes my expertise is greater than hers. For instance, in an earlier novel (After Gairech, 2021) I used hurley to refer to the game. My editor said hurley is the stick and the game is hurling. This is true, as far as it goes. However, Dublin slang calls the game hurley as well as the stick. |

Format Edit

What do I mean by format edit? Some might suspect I am talking about old-fashioned “galley proofs”, where a writer checks the printing proofs before the book is printed. This is not what I mean. The first time I published a book after it was in print I found a series of issues that neither my editor nor I had seen during the editing phases of the manuscript. Since then, I have taken to running an edit on both the eBook and the paperback versions of the MS. This catches issues missed during the editing stages.

The local proverb, “Vedi Napoli e poi muori” (See Naples and then die), appears on the cover of The Alcoholic Mercenary.

I use it as a running theme throughout the story. Both the protagonist and the antagonist touch on it. Rachel hears it at her leaving do, a joke in poor taste from one of her colleagues. She then questions if she has died when feeling the heat of Naples for the first time. Boccone thinks about it when things start down a steep and greasy slope.

The first time I heard it was in 1975 when my father yelled it jubilantly as we rounded a bend while travelling on the city ring road. Naples was laid out before us like an architect’s model.

But where does the saying come from, and what does it mean?

“Vedi Napoli e poi muori” is a local proverb about the city’s beauty and its surroundings. The popular belief is that Goethe translated it. However, l have heard it attributed to Wordsworth and even Keats, though Keats died in Rome without seeing Naples. Shortly after I first arrived in Lucrino in the early nineties, a local doctor told me he thought Keats was the first to translate the phrase. He is not the only one convinced that the poet visited Naples before he died. The saying is often considered to mean “see Naples before you die” rather than “you will never see better, so after seeing it, you might as well die.”

For me, personally, it goes much deeper. It is not only the city’s beauty and surroundings that are being extolled but also its rich history and the passion of its inhabitants.

Most would think of Naples as the sum of its parts: the start of the Amalfi Coast, the islands of Capri and Ischia, the ruins of Pompeii, to name a few. I believe there is much more to it.

Pozzuoli, where the bulk of The Alcoholic Mercenary occurs, is a town of beauty, but also frequently surprising gems of history. Originally founded as the Greek colony of Dicaearchia (City of Justice) by Greek emigrants, Pozzuoli was taken by the Romans during the Samnite Wars and became the city of Puetoli in c. 194 BCE. Much like Rome, the town is full of ancient architecture: Roman markets; a necropolis; an amphitheatre, which used to host sea battles because it was below sea level, but now sits above the town on a hill because of the bradisismic nature of the area (that is, the tectonic plates move up and down rather than from side to side, to the extent there is a sunken village called Tripergola out in the bay opposite the modern village of Lucrino, a real Atlantis). To say Pozzuoli is a hotbed would be an understatement because it sits atop Campi Flegrei (the Fields of Fire), a volcanic belt that runs around the gulf. Solfatara is an active volcanic vent at the top of a hill above the town. When the wind is in the wrong direction, Solfatara suffuses the area with a rotten egg pong. Although on first whiff, it is almost unbearable, over time it recedes so much, the locals barely notice it.

Oh, and what history the area has. Caligula had a bridge built from Pozzuoli to Baia because an oracle predicted he would ride a horse across the Gulf of Pozzuoli before he became emperor. A little like Hell will freeze over before Donald Trump is re-elected President.

(Terme-Baia: this is a photo I took from the balcony of a friend’s apartment)

In the photo, if you look over the station of Baia (where PO Jones was shot), on the left, under the just visible shadow of Vesuvius, is the port of Pozzuoli. Imagine a bridge extending that distance and Caligula riding a white charger across it.

Sulla had a holiday villa in Cumae, which sits on top of the bay facing Pozzuoli. The village of Lucrino is hemmed in by two lakes and a volcano. The largest of the lakes, Lago d’Averno (Avernus), was considered the entrance to Hell by the Romans, and many of the locals still believe it to be so. When describing it, they proclaim — in a hushed voice — that it is the deepest lake in Europe, if not the world, which is, of course, untrue — but no less awe-inspiring for all of that.

(Miseno: This is a photo I took from the top of Monte di Procida)

The largest fleet in the world (Roman) was stationed in the port of Miseno (in the photo), where the Coast Guard interceptor that caught Beni Di Cuma was stationed — opposite the port of Pozzuoli. The Sybil’s caves (beside Lago d’Averno) are thought by some historians to be the actual location of the Greek Oracle thought by most to be at Delphi.

Having lived there from the nineties to the naughties, my wife and I felt a great affinity with the sense of atmosphere engendered by its lively past and its passionate people. We would be there still if a medical emergency had not forced us to return to Ireland.

It is said that once you have seen the city of Naples, you can die peacefully since nothing else can match its beauty. Well, that is not the case in this book! Yes, the characters face death head-on, but there is not a lot of beauty in the underworld that is ruled by powerful organised crime syndicates. And hence we have the setting for The Alcoholic Mercenary by Phil Hughes.

I thought this story was wonderfully narrated. At times it felt like I was watching a movie rather than reading a book. It has all the ingredients of a bestselling crime thriller. The author has captured the era as well, the late 1970s may not seem that long ago to some, but so much has changed since then and it was interesting to read about a familiar world without all the bells and whistles that come with the modern-day. I especially enjoyed reading about Agent Rachel Welch and how she navigated a world where men dominated.

Although I enjoyed reading about Rachel I found it more difficult to connect with Boccone. He is one complex individual and as soon as I thought I had got a handle on his character he goes off and does something else. I guess his unpredictability helped move the story forward, but I did not care for him the way I did Rachel and I am not sure if the author wanted me to care for him. He is a loose cannon that can go off at any moment.

I think this book would certainly appeal to those who like historical crime fiction. It was certainly a good read and one I enjoyed very much.