It is self-evident that a novel needs a cast. It doesn’t matter if a book is a plot or character-driven story, there still needs to be those around whom the story revolves and evolves. Depth of character is paramount in the modern reader’s perspective. Having read hundreds of one-star reviews of books, a common theme has been characters who lack depth.

So, how do I add depth of character? Before getting into how I created the characters in TAM, I think I should outline what I feel makes a good character.

Good Character Profile

Many will tell you that you need to know what you are writing about, which is, of course, utter nonsense. How can writers of sci-fi or fantasy really know their subject? They can’t. They invent it. Still, others believe in the method acting approach: living as your character. I read “be your character” in one of the many articles I devour. It seems a little blasé and unrealistic. How can I be my character when I write pre-Christian Irish historical fantasy and Mafia-based murder mysteries? My characters spend their time chopping off heads, stealing and raping, drinking and debauching or shooting people who don’t pay their protection money. If I took a method acting approach to being my character — as the article author seems to be suggesting — I would not last too long this side of high walls with razor wire on top. But what did the author really mean? I am sure it wasn’t that I had to put on some plaid trouse, get out my longsword, and head into the hills of Ireland looking for a settlement to rob.

So, let me take a logical look at the theory you need to have experienced something to be able to write about it. No one has ever flown a dragon or a broomstick in a Quidditch match. I am also sure that most crime fiction writers have never committed a crime, at least not a crime that would make for an engaging novel. Personally, I think the key is different. I believe a good novelist requires a vivid imagination and extensive research. I am sure that Thomas Harris had no first-hand experience of sociopathic killers when he wrote the Hannibal books, but the depth of research in the character he created is patent. So much so, that Anthony Hopkins portrayed Hannibal so well, he got an Oscar after only sixteen minutes of screen time.

So, what does that mean in terms of character? In the end, it comes down to what, I think, is a simple list. Give characters realism; make them relatable; make them individual; give them conflict.

Realism

Characters must be realistic. Readers need to invest in them and believe in them. So how do we writers achieve that? There are several ways to make characters realistic. Not least would be giving them fallibility. Let them make mistakes. There is nothing more real than falling over occasionally. No one goes through life error-free. Take Gandalf, he went off and left Frodo alone with the ring, when he should have run for the hills, Frodo in tow, as soon as he suspected what it was. Then he led them into the mines of Moria, knowing there was something dreadful in them, but being too fallible to go against the wishes of the fellowship.

Make them complex. There is nothing less real than a one-dimensional character. There need to be layers that the reader can discover through the journey the character is making: their arc. Even the villains need the layers. Take Sergeant Troy in Far From the Madding Crowd; pure villain, but multi-layered, evidenced by his attempted suicide after discovering the death of his one true love.

Relatable

The reader needs to feel a connection to the characters. Even the bad ones need to garner a little sympathy or some understanding. To immerse themselves in the stories, our readers need to be able to say, “yes, that is an understandable reaction”, even when it is not something they would condone. This gives characters their humanity: the old Alexander Pope-ism about erring being a trait of humanity. Angus Thermopyle from Donaldson’s Gap series is a good example. The way he treats Morn Hyland is despicable, evil incarnate, for want of a better cliché. But the reader is given the backstory to Thermopyle’s evil, which, although it doesn’t excuse his actions, does go some way towards explaining them.

Individuality

Each character needs to be their own person. They need to have their quirks and their habits: a certain nuance in speech; a particular tic; a quaint turn of phrase: something that is unique to them. Henry Treece’s Heracles in Jason is a good example. Treece made Heracles a homosexual eunuch, which was a particularly unique take on the character, giving the story of Jason and the Argonauts another dimension. A slightly less well-known character, at least for now, is Inspector Laconto from the Time to Say Goodnight series: Laconto smokes Gauloises at murder scenes because he can’t stand the smell of death, a unique trait for a copper.

Conflict

Characters need to have troubles to overcome to generate interest in them. If they move from scene to scene without defeating any demons, then the story will be flat. It does not matter what those demons are, the inner demons of a character of literary fiction — such as Boccone’s alcoholism — or the fire breathing type from epic fantasy, conflict keeps the interest of the reader and, therefore, the pages turning.

So, How do I Create Characters?

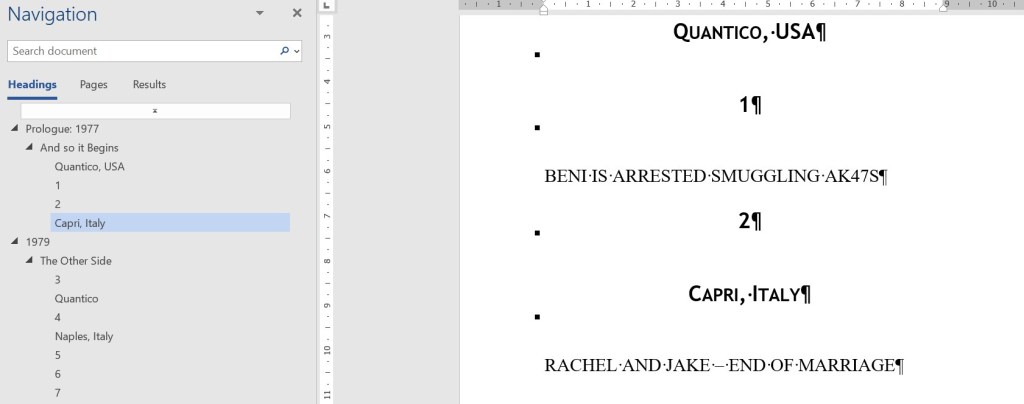

As I describe in Corkboard I first add a list of characters to my corkboard. At this stage, they are nothing more than a vague idea of a name and, maybe, a little backstory. Take the Alcoholic Mercenary, originally, his name was going to be Brando, but as the plot developed I found his brother’s name was Beni (short for Benito) and the names were too similar, so Nicolo was born.

Bio

When I have a list of characters, I create a bio for each of them. For bit-part characters, their bio is less detailed, but I do create one. The following are bios for TAM’s main protagonist, Rachel Welch and the main antagonist, Nicolo Di Cuma.

Rachel

She was born in Poughkeepsie in the mid-fifties. She had a turbulent time in high school, which impacts her day-to-day life quite significantly. She is driven because she will never allow herself to be forced back into her shell. She feels her husband let her down. She is a good-looking woman. When writing Rachel’s scenes, I envisaged Angelina Jolie in The Bone Collector, who was driven but unsure of herself.

At the beginning of the story, Rachel raises a barrier and comes across as hard and unforgiving. As the story proceeds the reader begins to realise it is a facade.

| I do find that my characters change while I am writing them. I don’t mean the change that is required as part of a story, but my ideas about them, their character, backstory, and so on. |

Boccone

Boccone was born in Pozzuoli in the late forties. In 1979, when the story is set, he is thirty (ten years older than his brother, Beni). His father was murdered in a clan war in the early sixties. When his father was murdered, his mother became an alcoholic, unable to cope with the struggle of bringing up two young sons. Driven by drunkenness, she became violent towards Boccone, eventually driving him to leave home and join the army.

When writing Boccone’s scenes, I envisaged Keifer Sutherland in 24 Season 8, when he became psychopathic after his love interest was murdered. Boccone has dark hair and complexion but is otherwise Jack Bauer in my imagination.